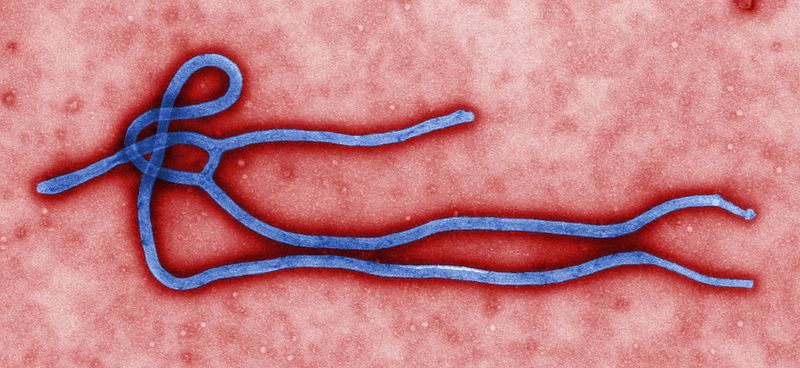

As much of the Christian community may be aware, two American missionaries who had been serving in Liberia had contracted the Ebola virus and are now being treated at Emory University Hospital. Before their departure from Liberia, however, they both had been given an experimental drug called ZMapp - Kent Brantly was given one dose, while Nancy Writebol was given two after her first dose did not have much effect. A missionary priest from Spain also recently contracted the virus, and is also being treated with ZMapp in an isolated hospital in Madrid.

So far, both of the Americans' conditions seem to be improving, but many people have been raising questions of ethics after this incident. These questions come from the nature of the drug, and also the timing in which it has been revealed to the world.

ZMapp is a drug that is being developed by a biotech company called Mapp Biopharmaceutical, located in San Diego. The drug takes the form of a serum, which uses antibodies from mice to fight the Ebola virus. Although the drug was successful when tested on primates, it had never yet been tested on humans.

Laura Seay recently posted on the Washington Post blog section regarding these ethical issues. "Why were Brantly and Writebol the only Ebola patients to receive ZMapp?" she questioned.

She went on. "Why hadn't anyone reached out to try the serum on Ebola patients sooner, especially if its potential to heal is so promising? Is the world of global public health really so biased toward the privileged that Americans get help while everyone else suffers? If nothing else, can we at least start giving ZMapp to as many Ebola-infected West Africans as possible?"

Jenny Jung, an undergraduate student studying biological sciences at the University of Southern California, had similar questions, and wondered why ZMapp had not been revealed until now. "It seems as if society considers two Americans more worthy, more deserving, more fitting to be cured than the 900 plus Africans, but in God's eyes, all [of these people] are His children," she said.

Some individuals wondered whether there were political issues involved in choosing to let Westerners have access to the drug, but not Africans.

A recent report by the SF Gate stated that ZMapp hasn't yet been widely tested because of its limited availability, and that the three missionaries were able to receive the experimental drug simply because the manufacturer agreed to release it to them.

"The World Health Organization is debating if any further limited supplies of experimental drugs should be used during the outbreak, and under what conditions," stated the report. "But the agency cannot force a manufacturer to go along."

Another student, who is currently studying dentistry, expressed that it actually may be better not to use the experimental drug on the wider population in Africa just yet.

"For the masses of West Africa, they're better off receiving fluids, first aid, and basic medical supplies than also taking ZMapp," stated Aaron Lee, a student at the University of the Pacific.

Dr. Tom Frieden, who is the director of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, expressed similar thoughts. He stated that "basic supportive care"”things like keeping patients dehydrated, maintaining their blood pressure, and treating any complicating infections"”can make a difference in survival," according to the SF Gate report.

Jung also expressed that it is important not to let the urgency to treat patients from "[blinding] us from thinking."

"If indeed ZMapp caused symptoms to worsen, we can blame nothing more than impatience and desperation," she said.

Onyenbuchi Chukwu, Nigeria's health minister, was reported to have said that he asked for access to the ZMapp drug but U.S. officials told him that the manufacturer would have to agree. Nigeria is the first country in West Africa to have asked for access to the drug.